Category Archives: Uncategorized

Response to “The Brisbane Effect: GOMA and the Architectural Competition for a New Institutional Building”

Lindsay Clare + Kerry Clare

March 2016

This paper seeks to redress and correct the inaccuracies and fundamental research deficiencies that underpin and plague the paper by Dr Naomi Stead, “The Brisbane Effect: GOMA and the Architectural Competition for a New Institutional Building” published in “Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand” (SAHANZ) in 2015 (1). The conclusions reached in that paper are not – as the author contends – “self evident” but rather appear to be self-serving. Stead admits to exclusive reliance on secondary sources, despite the availability of primary sources. This may indicate lack of rigour and curiosity or reluctance to engage with ideas and facts that would disturb an a priori proposition.

Our response might seem heavily weighted with quotes, however this is intentional, in order to demonstrate the differing and readily available views in print.

The range of inaccuracies in “The Brisbane Effect” also raises questions about SAHANZ’s approach to refereeing the papers it publishes.

In 2000 the Queensland Government announced an “architect selection competition” (run by Project Services) to identify a team of architects that demonstrated the capability and adaptability to work with the QAG – the end-user. This process is different from a design competition. The judging involved assessment of the design concepts and protracted interview sessions with the short-listed architects – the very purpose of which was to identify the architects best able and best suited to work with the Gallery as a cooperative and effective team on the project’s realisation. The competition was won by Architectus (design directorate: Kerry Clare, Lindsay Clare and James Jones) with Davenport Campbell.

The Queensland Gallery of Modern Art Architect Competition assessment panel members were:

Gary May, Deputy Director-General, Department of Public Works (Chairman)

Professor Michael Keniger, Queensland Government Architect

Professor Tom Heneghan, Professor of Architecture, Tokyo Kogakuin University

Doug Hall, Director, Queensland Art Gallery

Elizabeth Smith, James W Aldsdorf Chief Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

Advisers to QAG:

Peter Wilson, Director of Projects and Estates, Tate Modern, London 1972-2005

William Fleming, Coordinator, Building and Strategic Development, QAG

Michael Barnett, Project Officer, Building and Strategic Development, QAG

David Watson, Cinematheque consultant

Glenn Bourner, State Library of Queensland

Alan Wilson, Assistant Director, Management and Operations, QAG

Andrew Clark, Assistant Director, Curatorial and Collection Development, QAG

Andrew Dudley, Registrar, QAG

This paper has been reviewed by:

James Jones

Doug Hall

Michael Keniger

Tom Heneghan

Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper

As a trigger or catalyst for her examination into “The Brisbane Effect”, Stead cites a local newspaper columnist and refers to the building’s “architectural gestures”, before setting out to “explore whether:

“the place-specificity of the GOMA building was an article of rhetoric on the part of the architects themselves;

“an artefact of reception and media construction;

“or evidence of a more thoroughgoing state approach to cultural policy, as set out in the briefing and design philosophy in the architectural competition documents.”

A conversation with the architects would have clearly and factually answered these questions. However, the author avoided such a direct method of research. Instead, Stead jumps straight to the third enquiry – whether or not the state consciously sought a local solution – declaring in her introduction: “GOMA offers a fascinating example of converging discourses of art and architecture, state policy, identity, and the role of ‘place’ in constituting the museum as institution”(2); and from this it must apparently follow that state policy predisposed the procurement of regional architecture. Yet, given that the architects worked closely with Project Services, Arts Queensland and QAG, and corresponded with the then premier, over the six years it took to design and construct GOMA, we can categorically confirm that there was no “thoroughgoing state approach” or procurement of regional architecture driving the design. The State’s international and anonymous Architect Selection Competition was in fact devised for the opposite reason than Stead infers.

It should be noted that the short-listed teams were led by architects from Italy, UK, Sydney and Melbourne: none of the other schemes could be described as supporting the “regionalist” argument framed by Stead.

In the first stage of the architect selection competition the entries were anonymous, and all of the short-listed architects were interstate or international practices. Architectus was in Sydney. All five short-listed proponents were asked to collaborate with a Queensland-based practice to aid with delivery of the project should they be successful. We were later informed that the Architectus entry was thought to be from Japan. This confirms there was no local bias. The architects also learnt that when Architectus was short-listed, it was not known that the Clares were involved with that practice. Further, Kerry Clare started her architectural training in Sydney, and James Jones trained in Tasmania and Victoria. In our opinion Stead’s assertion that Architectus was a “decidedly local choice” is an egregious throwaway line she might easily have checked. Throughout the competition period, the architects at no time encountered any bias from government in favour of any particular “design style”. Stead’s conclusion that there was a state policy is more akin to conspiracy theory than evidence drawn from conscientious research. The Architectus design concepts of connection and place came from the design architects alone and were a natural extension of our combined (Clare and Jones) philosophy and previous works created over a sustained period.

Tom Heneghan, a juror, later wrote: “In the first stage of the architectural competition for GoMA, this was certainly the least provocatively, and possibly the most minimally, illustrated submission – comprising some small sketches and sketch plans, and a short block of text. Together, however, these conveyed a proposal of originality and astonishing sureness. One was left in no doubt that the architect’s apparently effortless resolution of this very complex and demanding brief was the result of a lifetime’s experience of designing such buildings.”(3)

Stead states that the Gallery Director, Doug Hall, favoured the Fuksas proposal but was “obliged to capitulate” to the other jurors and selection criteria. This depiction – indeed, any isolated singling out of preliminary jury discussions or opinions – misrepresents the role and function of a jury. Doug Hall has recounted that he was initially drawn to the Fuksas scheme but came to understand that it would not meet their functional needs, and so did not prefer the scheme. Hall has confirmed to us that he was not “obliged to capitulate”, and he takes exception to this description. The jury recommendation was unanimous. It was considered that “Architectus [+Davenport Campbell] offered the most robust and flexible schematic design, one which was capable of evolving and being refined in close consultation with the Gallery as client.”(4) Hall wrote, “in the case of GOMA, there has been an overwhelming national and international endorsement of the building: that it signifies a major cultural shift for Australia. It is not only the architecture and what it represents that is celebrated, but also the way in which it responds to the collections and programs that will shape the Gallery’s future. The building is elegant and grand without being pompous or threatening to visitors. Its physical and visual connections mark its relationship to a unique site. It is in every respect a public building – never to be confused as corporate, bureaucratic or residential.”(5)

Hall lobbied State government for a new gallery in the 1980s – this is technically when “the suggestion first emerged”. Various discussion and strategy papers were presented to Trustees about such a project, particularly from 1993 onwards after the conspicuous success of the first APT. A dedicated Project Unit was established within the Gallery in 1996. Hall continued fighting for the project that would become the GOMA through three successive premiers and changes of government. There was an earlier public announcement for a gallery competition made by the Queensland government in 1997. GOMA’s inception was well before the Guggenheim in Bilbao opened in 1997. These facts do not sit well with Stead’s version of history: “When the suggestion first emerged for a new gallery of modern art in Brisbane, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was the precedent on everyone’s mind, given that it had opened only three years previously.”(6)

In our 2010 AS Hook address, we outlined our position about authenticity in relation to our work. “The connection between public buildings and community identity is strong. Public image is the common mental picture carried by the majority; our view is that public buildings have a responsibility to be essential to place and of enduring significance. The interconnection of public buildings with the fabric of a town has historically been the product of design commissions undertaken by architects. For example (as documented in the study by Don Watson and Judith Mackay) many architects in Queensland country towns who were involved with the design of houses were also commissioned to produce public buildings during the progression of their careers. This provided continuity and the essential link with the culture of the town.”(7)

Richard Serra emphasises how important it is for a cultural building to connect to place. Speaking of museums, he observed that “in response to the tendency for architects to treat their buildings as if they were autonomous works of art … museums, rather than just being containers for historical artefacts, or showpieces of architectural acrobatics … [should] try to foster dialogue and allow for an exchange of ideas and views …and further … relate architecture to its locality, to the larger framework of a city”.(8) This is a notable plea from an internationally recognised artist.

In 2013, in a symposium paper, Lindsay Clare stated: “The opportunity to enrich the cultural life of Brisbane was provided through the creation of an open, inviting, generous and democratic ‘urban pavilion’. The siting of this pavilion was both a logical and intuitive response to the curve of the river that is in dialogue with the city and stands at the threshold of the cultural precinct, and further, “A stated objective of the design brief was to create ‘a unique cultural experience’. It is always possible to import ideas borrowed from other places but they may not be relevant or appropriate to a place, or authentic to culture. This understanding is critical and important over time if the concepts are to be sustainable.”(9)

Stead also broaches issues of budget. While it is difficult to gain a sound understanding of the shifts that have occurred in building procurement over the last two or three decades in Australia, again, this matter could easily have been clarified in discussion. The building budget was published as $71.858 million in the Gallery’s publication dated 2002(10); and “$100 million plus (including fees), or just over $4000 per square metre” in the Gallery’s publication, “GOMA Story of a Building” dated 2006(11). The full budget figures were never expressly given to the architects, and were subject to a contract between Lend Lease and Project Services. There is often confusion between total project budget and the building budget. The State government stated that the project did not go over budget. The winning scheme met the government’s budget. Quantity surveyors verified the costings through the competition stages. After the competition, the government called for tenders to select a managing contractor to work with the architects through Design Development to ensure budgets were met. DD was undertaken with the selected tenderer and during that stage, costings were met. When completed in 2006, GOMA’s cost per square metre, as built, was reportedly 49 per cent less expensive than Federation Square, completed four years earlier, and 28 per cent less expensive than the New Asia Wing at the AGNSW which was completed three years earlier. GOMA was delivered at a time when construction cost escalation was reported as between 11-15 per cent per annum in Queensland. There was no allowance for escalation in the agreement struck by the government with the managing contractor, therefore the building’s budget was effectively reduced during the procurement and construction stages, affecting areas, materials and detail.

In Stead’s second enquiry – the building’s reception in the popular and architectural press – she selected articles that serve her purpose. But since the completion of the project some ten years ago, there have been a number of articles (not cited in her paper) that do not fit her construct. Since her enquiry is about rhetoric and the part it plays in the consciousness of a community, it would seem not unreasonable to explore a wider, balanced selection of published material. While the popular press often prints a simplified version of a more broad discussion, there are other publications – products of substantial and detailed research – that have demonstrated the progression through history of residential and public architecture within the region. For example, Michael Keniger wrote in 1990, “putting aside the form and formula of the Queensland house, its qualities of simplicity, rational construction, economy and elaborate enrichment by light and line may also be found in the public buildings and towns throughout the state.”(12) Alison Smithson six years earlier wrote in Architecture Australia of the distinct character of early Queensland public buildings.(13)

Now, to visit Stead’s first enquiry: that “the place-specificity of the GOMA building was an article of rhetoric on the part of the architects themselves”. The most obvious omission, or perhaps leap, in Stead’s argument here is her contention that the architects support the idea of the building as a scaled-up vernacular house. Stead unashamedly misrepresents our position, and has overlooked or not understood our own writings. For example, the notion that a large roof should slope downwards in emulation of traditional buildings – “to create a low shaded edge, in the way that every Queenslander verandah does”(14) – is, in our opinion naive and simplistic, lacking in a grasp of climate responsiveness one might otherwise expect from architectural academia. GOMA’s roof forms respond to many issues of site, environment, space and indeed the shortcomings of traditional Queensland buildings – such as dark interiors and poor balance of light (partly ameliorated by screens). These comments also, by way of association, are dismissive of the many significant, varied and liberating works produced by contemporary Queensland architects.

The QAG, designed by Robin Gibson in 1973, continues to serve as an excellent gallery. However GOMA’s architects observed, as others did, that this white modernist building had no edges offering shelter from Brisbane’s subtropical glare, heat or rain, and the surrounding public space could not be comfortably occupied. The potential for connection is a key role for a contemporary gallery. This has to be balanced with the need to protect the art to achieve international gallery standards. GOMA’s openness sets out both to engage with the public and locate it within its context. Heneghan wrote, “GoMA’s unusual architectural porosity and openness provide a powerful and physical connection between the gallery and the city it is part of. The ease with which the public can just wander into their gallery helps bridge any gap between them and the collection … This sense of connection to, rather than separation from, the exterior is a very considerable achievement.”(15)

Stead then condescendingly associates the roof with a European example, asserting “in fact it is closest of all to a particular thread of contemporary buildings, including Jean Nouvel’s Lucerne Cultural [sic] and Congress Centre”(16) – an erroneous notion one might forgive in the popular press. Stead’s observation appears to mirror a quote from an article by John Macarthur; “The screw of this little paradox turns more tightly for architects who know that the form of the building and particularly the flying roof and the box-like irregular protrusions are greatly inspired by Jean Nouvel’s Lucerne Cultural [sic] and Congress Centre.”(17)

The resolution of the Gallery’s roof answers QAG’s brief and site conditions. This resolution also corresponds with the architects’ desire for the public to connect with the building, made easy through its sheltered edges, and as stated earlier is consistent with our and Jones’s philosophy since the late 1970s.

During the competition phases, initial designs incorporated columns to support some roof edges – in other words, quite unlike the Nouvel building. However in discussion with the Gallery, we developed the design to provide unencumbered views to walls in order to increase the potential uses of those walls for artists and curators. (Images of the model showing columns are readily available in the QAG 2002 publication, Queensland Gallery of Modern Art Architect Competition.)

The box like protrusions came from the conceptual idea of a chest of drawers to allow planning flexibility: “The three dimensional planning method that has been employed in the schematic and design development phase is analogous with a ‘chest of drawers’. Major spatial changes have been made, across the briefed range of accommodation requirements, in response to the rigorous client brief, budget restrictions and design development process, without diluting the architectural idea.”(18)

Heneghan, a UK-trained architect and academic (now at Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku), understands the building, its roof and its place more readily than some local academics.“Seen in these terms, the commitment of the Government of Queensland, which nick-names itself ‘The Smart State’, to the construction of the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (or GoMA) – the largest gallery of contemporary art in Australia – is perceptive. It also means that GoMA must be assessed not only for its achievement of its core function, but also for its achievement of iconic status – which was a pre-requisite of the client’s brief – as a symbol of the cultural and social ambitions of its region. But, while GoMA is certainly an icon for or of its region, it is wrong to think of it as a ‘regional’ icon. The too-often-repeated alleged-witticism that GoMA is ‘a Noosa weekender on steroids’ is, at best, feeble – based, very tenuously, on some supposed up-scaling of the idea of ‘the veranda’. But, this notion of the ‘inhabited edge’ does draw attention to a very crucial way in which GoMA re-defines its own building-type. ‘Icon’ buildings tend to be, almost by definition, self-centred. But, GoMA reaches out to, responds to, and sometimes even defers to the very differently-nuanced open spaces which surround it. By this, it side-steps the quasi-sanctity and incongruity which are the usual characteristics of iconic architecture, and it becomes, instead, iconoclastic – a characteristic which is central to the gallery’s mission”.(19)

Some six years later, Giles Nolan echoes Heneghan’s observation: “Seemingly out of nowhere Brisbane had stepped into the international arts arena – and thanks to Goma it was packing a mighty punch. A key reason that Queensland’s state government established Goma was to create a larger home to accommodate and expand the APT, the world’s only major contemporary Asia-Pacific region art series. The buildings’s purpose, however, has extended well beyond this brief; the space has redefined Brisbane as a cultural destination.”(20)

Stead also refers to an article by Andrew Leach to support her position regarding a “disjunction between rhetoric and reality”(21). Leach’s dislike of the building appears to cloud his understanding of a number of the operating architectural elements. His pejorative descriptors such as “homely”, “domestic” and “decorative”, then “gigantist”, and glib reference to an Italian newspaper’s forgivably sensational or amusing title “Una splendid ‘Beach House’” are, in our opinion signs of a muddled point of view. Leach disparages the “widespread decorative and functional use of hardwood batons [sic]”(22): these hardworking timber screens purposefully filter glare; reduce heat load; create transparency/surveillance in and out of the offices; provide horizontal views from within and achieve some uninterrupted views of the river and city where the screens angle out to the north; and provide a counterpoint to the protective walls of the galleries. The screen stops below the roof allowing the upper uses (art conservation) to moderate light from within, as required by the brief. Timber elements throughout the building are consciously used for their tactility, the worked surface of timber having universal appeal without limiting or overpowering the needs of the artists and curators.

While Leach also bases some of his assumptions on articles in popular media, his opinions differ from other critiques (including but not limited to those of Beck and Cooper, Heneghan, Hall, Jackson, Frampton, Xu, Hyatt, Price, Stapleton, Thomson, Noble, Giles, Kirkland) on matters of scale, materiality and civic role. In our opinion Leach betrays no understanding of the brief’s spatial requirements for a truly flexible and responsive gallery of modern art that meets international exhibition standards. He seems unaware of the vast differences in gallery types. GOMA is not a portrait gallery, museum for a fixed collection, or private collection. Simon Wright, Assistant Director noted, “Goma has a magnificent exterior but the interior is its real magic because the space and volume that we get to play with here is unparalleled in the southern hemisphere”.(23) Photographer Douglas Kirkland in speaking to local press said that although he has had big shows all over, from Moscow to Paris and across the United States, he has never had the opportunity that the spaces of Queensland Art Gallery’s Gallery of Modern Art are now offering. “The city of Brisbane has something amazing here … I hope people know what a high level of sophistication this gallery is. It makes me feel like I’m in a cathedral, enveloping me in the most exciting way.”(24) Beck and Cooper describe the building’s disposition as “(Extra)ordinary: The form of the building projects an image of GoMA as friendly, welcoming and extrovert. With its large overhanging roof, open verandahs and timber batten screening, the building conveys a typical, familiar and regional expression of subtropical informality at a civic scale.”(25)

Stead also notes “But the architects’ original intention that the glass cladding which encases much of the museum would provide a space for digital interactive artworks was never realised – leaving a largely blank, opaque glass wall on the southern façade, facing the main approach”(26) whereas the translucent glass facade is designed and constructed as series of light boxes with accessible cavities and each including power and data. This facade has already been used for temporary art works and is currently being prepared for a more permanent piece. On the same page Stead says, “Likewise the first-floor outdoor walkway running the length of this wall is never used, its access doors kept permanently closed”, however the doors are predominantly open, and closed only during certain exhibitions or occasions – as confirmed by the Gallery. The Level 2 balcony is used as part of the Gallery’s fund-raising activities.

Through the integrated approach to the design of GOMA, environmentally sustainable design underpins the architects’ proposals for siting, plan form, construction, detailing and operation of the building and its services. The benefits that flow from this approach include significant reductions in energy use, running costs and carbon emissions for the gallery type – something the Gallery actively sought from the final design solution; improved comfort for visitors and staff; and the porosity and connection to site noted by Heneghan. Ché Wall of Advanced Environmental Concepts, and world leading environmental engineer, headed the services design team. The climate responsiveness of the building can be numerically quantified – and in the case of staff and public comfort, anecdotally substantiated – unlike the unverified opinions offered by Stead. Beck and Cooper wrote, “Possibly the most overt intention in their designs is the impulse to incorporate climatically responsive, low-impact environmental control systems … [A]n historical perspective shows that the Clares always approached design from this position, years before climate change entered public consciousness. For them it has been a Modernist act of architectural determinism.”(27)

In a demonstration of circular logic, begging the question by positing the preconceived outcome within the enquiry, Stead confidently concludes: “So as we have seen, the rhetoric of the architects themselves, as well as accounts from both the popular and architectural media, served to frame the building as a kind of scaled up vernacular house”(28). She digs herself in deeper: “In the end, the apparent climate-responsiveness of the building itself is really only an image”(29) – that is, it is rhetoric. However the Gallery’s clear environmental initiatives are published in “Art House Gallery of Modern Art Queensland”.(30) They include: Daylight to galleries, reflected and direct daylight to deep internal spaces, shading – roof overhang and fixed elements, river heat rejection – use of EPA approved chemical, eliminated cooling towers, creates all chilled water requirements, saves water, reduces risk of legionella, floor based displacement air conditioning – increased indoor air quality, reduced energy, materials – use of sustainable timbers, T5 lighting for offices, glazing selections driven by thermal comfort/mechanical load reduction, construction practices – reuse of concrete and bitumen from demolition, on site use of remediated landfill, steel reinforcement from demolition separated and recycled, porphyry stone from site donated to council, silt barriers from unwanted site vegetation (wood chipped).

80% of the building waste generated was recycled. This is noted in the Arts Queensland 05/06 Queensland Art Gallery Annual Report.

Stead’s conclusion is without basis in fact. It cannot be substantiated. As the author admits, she has relied exclusively on secondary sources, and her paper makes painfully plain the pitfalls of failing to interrogate primary sources, the key protagonists involved in the project’s design and realisation.

The architects do not and have never framed the building as a scaled-up vernacular house, nor have we “served to frame the building” as a scaled-up vernacular house. Our commentaries on the building, if interrogated, do not lead to this conclusion. Stead’s conclusions would appear to be drawn exclusively from observations made by the popular media, unleavened by a single primary source and certainly not by any comments from the architects or the client. She states, “As we have seen, there is indeed evidence that the architects’ own account of the building played into popular media descriptions”.(31) However she provides no evidence to substantiate this statement. Stead’s use of the term architects’ “rhetoric” is problematic: rhetoric means false, insincere argument; or “[it] is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the capability of writers or speakers to inform, most likely to persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations” (Wikipedia). There is no evidence in her paper to support her proposition that we have used “rhetoric” such as stylistic falsity of design references to the Queenslander, or endeavoured to persuade or inform an audience of this premise. Similarly, she provides no evidence of a State cultural policy (ie, favouring references to a local vernacular style). As noted above the State’s international and anonymous Architect Selection Competition was devised for the opposite reason to the one Stead infers.

Stead’s paper, in our opinion demonstrates a disturbing lack of rigour on the part of an academic. Her extensive use of secondary sources has led to incorrect statements and suppositions, and to conclusions drawn from false premises. Had she looked at the written and built works of the design architects, or communicated with them, or with the Gallery director or any member of the assessment panel, she would have arrived at a more accurate historiographic account. It’s like writing a biography without bothering with the messy impressions of those who are still alive and kicking and who knew the subject in detail. But a different approach, investigating primary sources, might have disturbed Stead’s idée fixe.

1. Stead N, “The Brisbane Effect: GOMA and the Architectural Competition of a New Institutional Building”, in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32 Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, pp 627-39, Sydney, SAHANZ, 2015

2. Stead N, op cit, p 627 ! ! 5 of 6 19 20 21 22 23 24

3. Heneghan T, “Gallery of Modern Art”, in H Beck and J Cooper (eds), Architectus— Between Order and Opportunity, ORO Editions, California, 2009, p 187

4. Queensland Art Gallery, Queensland Gallery of Modern Art Architect Competition, 2002, p 19

5. Hall D, Director, QAG/GOMA, letter to Lindsay + Kerry Clare, 5 March 2007

6. Stead N, op cit, p 636

7. Clare L, Clare K, AS Hook Address, Architecture Australia, Vol 100, No 1, January 2011

8. Serra, R in conversation with Alan Colquhoun, Lynne Cooke and Mark Francis, in Kunsthaus Bregenz. Edelbert Köb (ed), Museum Architecture/Texts and Projects by artists (pp 85-97, English; pp 89-103, German). Bregenz: Kunsthaus Bregenz, Archiv Kunst Architektur, 2000

9. Clare L, Clare K, “The Cultural Connection, Studies in Material Thinking”, paper delivered at UNSW Museum Symposium, 2013, https://www.materialthinking.org/papers/188, 0130_SMT_Vol12_P06_Clare_- FA2.pdf

10. “Queensland Gallery of Modern Art Architect Competition”, Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2002, p 33

11. “GoMA Story of a Building”, Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006, p 39

12. Keniger M, Rex Addison, Lindsay Clare and Russell Hall, Australian Architects 5, RAIA, 1990, p 4

13. Smithson A, Architecture Australia, Vol 73, No 1, 1984, p 60

14. Stead N, op cit, p 633

15. Heneghan T, op cit, p 187

16. Stead N, op cit, p 633

17. Architecture Australia, March/April 2007, “State of the Arts”, p 52

18. QGMA Schematic Design Report Volume 1, section 5A.1.1 architectural design, p 2

19. Heneghan T, op cit, p 186

20. Nolan G, “Art Smarts Brisbane”, Monocle, Issue 75, 2014, pp 151-55

21. Stead N, op cit, p 634

22. Leach A, Architecture New Zealand 2, “Too Bold to be Faithful?”, 2007, pp 54-61

23. Wright S, Nolan G (author), “Art Smarts Brisbane”, Monocle, Issue 75, 2014, p 155

24. Sorensen R, “Douglas Kirkland: his camera doesn’t lie”, The Australian, July 10, 2010 http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/douglas-kirkland-his-camera-doesnt-lie/story-e6frg8n6-1225888373398

25. Beck H, Cooper J, Fleming W, GoMA: Story of a Building, Queensland Art Gallery, Australia, 2006, p 17

26. Stead N, op cit, p 633

27. Beck H, Cooper J, UME Clare Design Works 1980-2015, ORO Editions, California, 2015, p 19

28. Stead N, op cit, p 637

29. Stead N, op cit, p 637

30. Hyatt P, “Art House Gallery of Modern Art Queensland”, Thames and Hudson Australia, 2008, p 33

31. Stead N, op cit, p 637

Architectural Steel Innovation

Studies in Material Thinking: Material Thinking of Display

Full article: http://www.materialthinking.org/papers/188

Volume 12 Material Thinking of Display

Cultural Connection—The Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA).

Architects: Architectus (Lindsay + Kerry Clare—Design Directors 2000–2010) with James Jones. Lindsay and Kerry Clare

Faculty of Design and Creative Technologies Auckland University of Technology Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Abstract: There is a growing desire for the architecture of galleries and museums to create a strong identity for their institutions. We argue that this identity can spring from an understanding of context and culture to achieve authenticity, connectedness, individuality and meaning. A response that favours particularisation and locale can also engage with global concerns and opportunities to create a unique cultural experience. The process for procuring and constructing new gallery buildings needs to support this architectural approach. The unique attributes and potential of any region or country are most often derived from topography, climate and social and cultural backgrounds. Relevant architectural responses to these attributes can often be found in historic or vernacular buildings. To add to the complexity, we consider that the identity of a gallery building should not be achieved to the detriment of the fundamental needs of the gallery, that is, functionality, flexibility and the ease of connecting people with art.

Introduction: There is much discussion about museum architecture acting as a magnet to help a city or region develop a strong identity or reputation. Whilst a strong architecture can greatly enhance or enrich a visitor experience, there has been a tendency for some evocative works to emphasise architecture at the expense of the art. In this regard our design brief from Arts Queensland was extensive and thorough—a document of around 170 pages.

The design brief contained a detailed technical description of all spaces required along with their respective relationships. Also included was the philosophical underpinning and research undertaken to support technical requirements and museological and curatorial practice. The gallery brief underscored the importance of context within the cultural precinct, the city, and to the broader Asia Pacific region.

Our interpretation of this brief was assisted by extensive meetings and communication with three nominated client representatives; Doug Hall (Gallery Director), William Fleming (Coordinator Building and Development) and Michael Barnett (Senior Project Officer). We reported to Hall, Fleming and Barnett, who represented the Trustees and the needs of staff, curators, artists, government and the public. They had produced the brief over a number of years of planning, research and consultation. It is acknowledged by the Queensland Art Gallery that hundreds of people contributed to turning the idea for a new gallery into a reality. Major contributing factors that significantly shaped the success of the project included continuity (cultural memory) of key personnel from the government as well as the architects. This continuity was critical in maintaining agreed conceptual principles throughout the delivery of the project. Throughout the project, there were many changes in personnel within government as well as Lend Lease, the managing contractor. Not all newcomers to the project were aware of important decisions, principles or ideas previously proposed and agreed. Some claimed full understanding of the project after spending two hours viewing drawings and reading the brief (after we had spent two years working on the project with the end user client). Some newcomers brought different agendas that did not support the brief.

An art gallery is a public building. Its significance for the public consciousness is characterised by the fact that it returns enclosed public space to the city. In keeping with this view our proposal envisioned the role of an art gallery as a place for people to connect with art, in all its facets. The opportunity to enrich the cultural life of Brisbane was provided through the creation of an open, inviting, generous and democratic ‘urban pavilion’—created by the ease of access, visibility to the interior and connectivity. The siting of this pavilion was both a logical and intuitive response to the curve of the river that is in dialogue with the city and stands at the threshold of the cultural precinct which comprises the Gallery of Modern Art, the State Library Queensland, Queensland Art Gallery, Queensland Museum and Queensland Performing Arts Centre.

A stated objective of the design brief was to create ‘a unique cultural experience’. It is always possible to import ideas borrowed from other places and situations but they may not be relevant or appropriate to a place, or authentic to a culture. This understanding is critical and important if the concepts are to be sustainable over time. We feel very strongly about responding to the specifics of place—which is not a limiting factor, rather a springing point. Design can be used to particularise, enrich, embellish, complement and heighten our understanding of place. In a time of globalisation local understanding can be a powerful counterpoint to facilitate authentic engagement and experience.

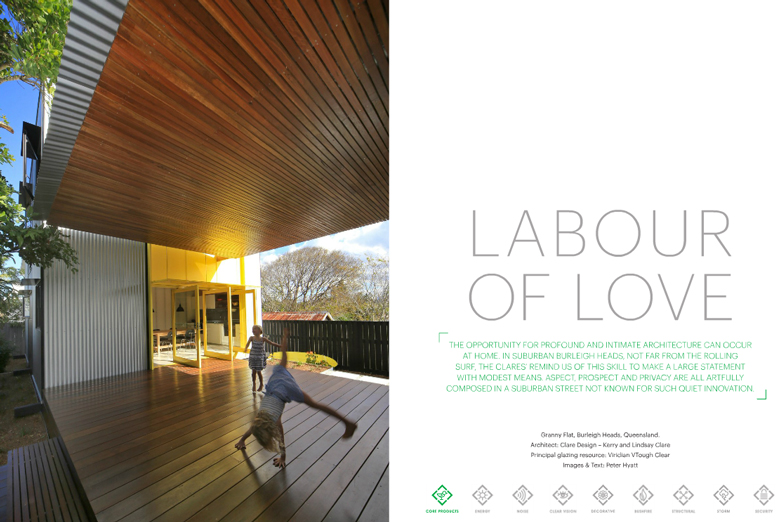

Labour of Love

Clare Design: Works 1980-2015

Full article: http://www.oroeditions.com/book/clare-design/

Book review by Elizabeth Musgrave

Daily Dose of Architecture Review

Overview:

In 272 pages, with photos and drawings (including design and construction details) Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper show 30 environmentally sustainable buildings spanning 35 years of the practice of one of Australia’s foremost architects, Clare Design. The Clares, practising as architects on the far side of the world, approach their work with a philosophical position that produced beautiful, climatically responsive, low-impact, environmentally sensitive buildings. They achieved this working not from a body of widely accepted theory and practice but from first principles, applying native can-do empiricism to their designs. These buildings – made in partnership with clients – are demonstrations of this architectural philosophy. Almost from the inception of their practice, their work was recognised and commended by their peers with architectural awards. Over the years their elegant and climatically sensitive buildings have been the subject of exhibitions, magazine articles, both popular and professional, and several books.

About the author:

Lindsay and Kerry Clare. Clare Design was established in 1979 on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland. Lindsay + Kerry Clare, a husband and wife team, have been producing architectural projects for more 35 years. Their work has been consistently acknowledged at home and internationally, for design excellence and environmental performance. Haig Beck + Jackie Cooper write, “The Clares’ ideas about experiencing natural light and ventilation are merged with their ideas about typology. They fuse ideas about type and climate into building form. Their buildings allow occupants to engage with architecture and the world outside, reinforcing the essential connection with place.” They received the RAIA Gold Medal in 2010.

Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper. In 1976 Haig Beck was appointed editor of Architectural Design magazine. In 1979 he and Jackie Cooper launched International Architect magazine in London. They returned to Australia in 1986 and have continued collaborating as architectural editors, critics, writers and publishers. In 1996 they launched UME magazine. The output of 40 years of writing includes books, chapters, articles and critical reviews. Most of these have been jointly written.

Improving the Quality of Housing

Full article: http://architectureau.com/articles/improving-the-quality-of-housing/

In this essay from Architecture Australia May/Jun 2014 , Lindsay and Kerry Clare explore the impact of SEPP 65 on the quality of multi-residential design in New South Wales.

Like city streets, housing can be considered to be the framework for life. Just as successful cities have great streets, good housing can provide opportunities and influence the way we live, work and enjoy our lives. Quality and choice are what set both a city and housing apart.

The desirability of cities is re-emerging. Through informed analysis, many progressive city councils have a clear understanding of what makes their city work for its people. As the late planner and landscape architect Ian McHarg said, if you prioritize issues by importance, it becomes very easy to make decisions.1 The ingredients of a good city – connectivity, opportunity (choice), environment, economy and culture – can also be, at a smaller scale, the ingredients of good housing.

Since 2002, multi-residential development proposals in New South Wales have been assessed under the State Environment Planning Policy no. 65 (SEPP 65), which measures quality in relation to urban response, environment, landscape, social contribution, amenity and aesthetics. This policy has arguably been the biggest step forward for improvements in Australia’s housing stock and, in a relatively short time (for the construction world), has led to measurably better outcomes. Its precedents include the 1992 Australian Model Code for Residential Development (AMCORD) and the Residential Flat Design Code (RFDC), though unlike these earlier codes, SEPP 65 is embodied in state policy and assessed through independent design review panels. Panel reports are presented as advice to the relevant approval authority. SEPP 65 review panels are able to assess the functional aspects of each brief, site and context and provide independent recommendations to council beyond the overall planning requirements, which often cannot respond in particular detail to the constraints and opportunities of each site. It also encourages meaningful interaction between architects, landscape architects, urban designers and planners and approval authorities.

Research, feedback and anecdotal evidence all point to the policy’s success. Harry Triguboff, the founder and managing director of residential developer Meriton and the sixth richest person in Australia according to Business Review Weekly’s 2013 “Rich 200” list, has been noted to say that Meriton has “done well” since the introduction of SEPP 65, with apartments [of better quality] selling better. A survey conducted by the Property Council of Australia seven years after the introduction of SEPP 65 showed that 82 percent of respondents agreed that it had led to improved design, and with relatively minor impact on affordability.2 The dividends from good housing are very broad and, as with city planning, good intent can have positive knock-on effects. Increased opportunity, satisfaction, security and wellbeing all stem from the quality of the built environment. Some have called for an extension to SEPP 65 covering townhouses and other smaller scale housing types to improve housing stock across the board.

SEPP 65 has helped to reduce the impact of self-interested, random and uninformed opinions on housing outcomes and has preferenced informed review for the sake of “the greater good.” It has also established a critical distance between the vote-seeking local councillor or small self-interest group and more holistic approaches to urban design.

SEPP 65 also opens the door to discussions about aesthetics and the visual contribution each building makes to the city and to people’s lives. SEPP 65 also opens the door to discussions about aesthetics and the visual contribution each building makes to the city and to people’s lives. This is a step forward from previous policies, which either opted for a “hands-off” approach or overplayed contextual requirements and favoured historic references. Architecture and Beauty author Yael Reisner has argued that since the early modernism of the 1930s, architecture has continued to eliminate aesthetic bias: “When the self is removed beauty is avoided, leading to alienating built environments. For this reason we should desire beauty as a motivation for exploring architectural languages that could affect people, a notion to which architecture has been detrimentally resistant.”3 Without restricting creativity, panels can consider the role of the building in the public realm, the need for “signature” or “quiet,” or other aesthetics and their effects on the streetscape. SEPP 65 provides an avenue for robust discussion about aesthetics and their role in the culture and identity of a city or part of a city.

A city’s housing mix also encompasses affordable housing and student housing – two typologies that aren’t currently covered by SEPP 65, though its principles could easily be applied. Providing a balance of housing types close to employment and transport options needs to be fostered and monitored through planning controls. Other housing types such as “two-key” apartments (a larger apartment that can function as two separate living units), “Fonzie flats” (studios above garages) and granny flats cater to a variety of extended family or community living needs that are again becoming common. As house prices rise, people are appreciating the benefits of multi-generational living and, as a result, the instance of families of up to four generations living under one roof is increasing. Meanwhile Defence Housing Australia, one of the largest housing providers in Australia, is looking at better ways to accommodate the changing defence family demographic: to support their interests and their growing families, to provide companionship through community and to balance the need for privacy with the need for connection. The high turnover and posting rate of defence families necessitates systems and homes that facilitate an easy transition to new places and new cities.

Another pressing issue that is being discussed through SEPP 65 is the need for greater provision for open space. Deep soil for viable trees (with no basement or other obstruction below the ground) and rainwater filtering will always be important for the environment with regard to air quality and reduction of heat build-up in urban areas. A large tree shading a facade can reduce internal temperatures by up to fifteen degrees. Both transpiration and shading from trees have a marked effect on microclimates and the inclusion of small pockets of deep soil in building developments is just as important as aggregated deep soil areas for improving the environmental performance and amenity of urban areas.

Cars and their effects on cities and housing have long been cited as the cause of problems including social isolation, obesity, air and noise pollution and urban decay. The late Melbourne architect Col Bandy often remarked that the car had allowed us to ignore the density that makes a city work. As the quality and vibrancy of inner-city and urban areas are regaining appreciation, the place for the individual private vehicle is being reduced and, in some areas, actively restricted. Carshares, bikeways (with family-friendly and commuter routes), tramways, self-driving cars and electric vehicles – to name a few – will all contribute to better streets, better air quality, noise reduction and increased amenity. Housing may always need to provide some storage for cars but the extent could be greatly reduced and, in some areas, eliminated. Consider how the voids formerly occupied by driveways and on-grade parking might be used in the future – and how less disrupted our public spaces and street frontages would become.

The regeneration of cities and the rising appreciation for housing density is an important topic on many levels. A well-worn quote from former Archbishop of Paris Jean-Marie Lustiger is worth reiterating, and that is: “that if all humans were gathered around Notre Dame of Paris with the same density as on the banks of the Seine, they would make up a circle with a radius of only a few hundred kilometres.”

The housing being built today could conceivably be occupied for more than one hundred years, which makes flexibility an essential part of their design. Regardless of type, generally the most enduring buildings have a good measure of openness, clear structural spans, good ceiling heights and access to light and ventilation – “offering opportunity rather than giving direction,” to quote Michael Benedikt.5 A good example is the old-school classroom: the generously sized rooms, complete with high ceilings and passive solar design, remain useful and desirable and can easily adapt to new teaching methods. In a similar way, housing should avoid being too prescriptive when different households and different eras will have different demands. Simple planning decisions such as the placement of wet areas, kitchens and doorways can greatly affect how space can be used and should be made with longevity in mind. Houses have many lives. Rather than meeting a designer’s idea of “perfection” (a word derived from the Latin word for “complete”), housing should aspire to facilitation.

1. Ian L. McHarg, Design with Nature (Garden City, NY: Natural History Press, 1969).

2. Glenn Byres, NSW executive director of the Property Council of Australia, in a letter to the NSW Department of Planning and Infrastructure, 19 July 2011 (citing survey results from 2009). propertyoz.com.au/library/110719%20Letter%20re%20SEPP%2065%20and%20RFDC.pdf (accessed 3 March 2014)

3. Yael Reisner, “Do architects have a problem with beauty?”, Building Design online, 10 September 2010. bdonline.co.uk/do-architects-have-a-problem-with-beauty (accessed 3 March 2014)

4. Jean-Marie Lustiger, Caritas Australia Helder Camara Lecture, Melbourne, 2001.

newman.unimelb.edu.au/calendar-events-and-alumni/2001-lecture-series

5. Michael Benedikt, For an Architecture of Reality (New York: Lumen Books, 1987), 52.

Grand Civic Ambitions: Library at the Dock

Full article: http://architectureau.com/articles/library-at-the-dock/

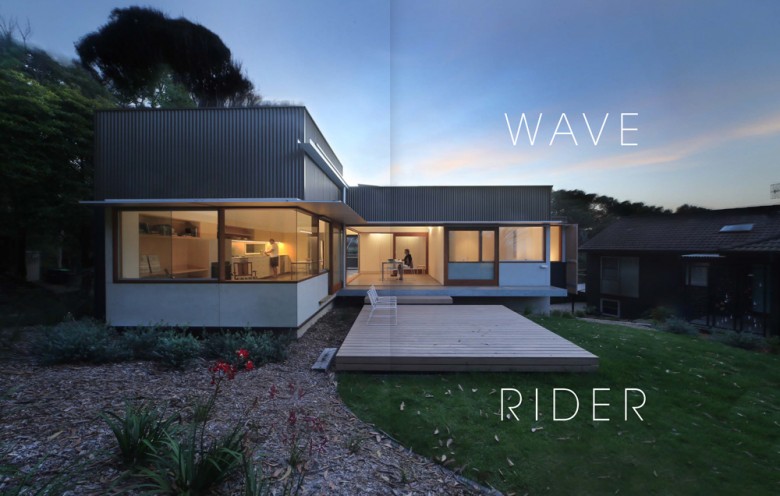

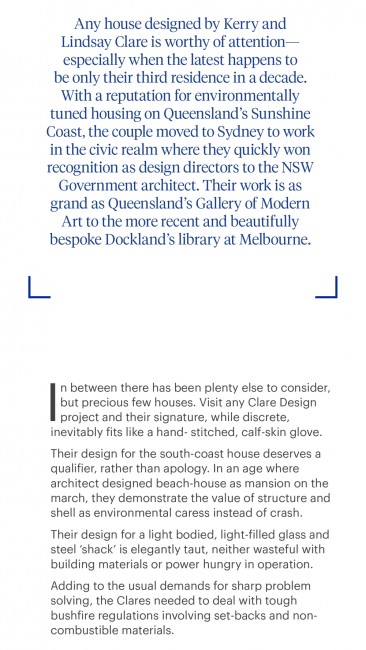

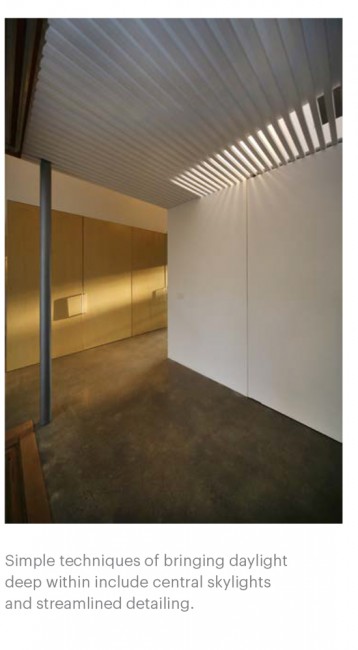

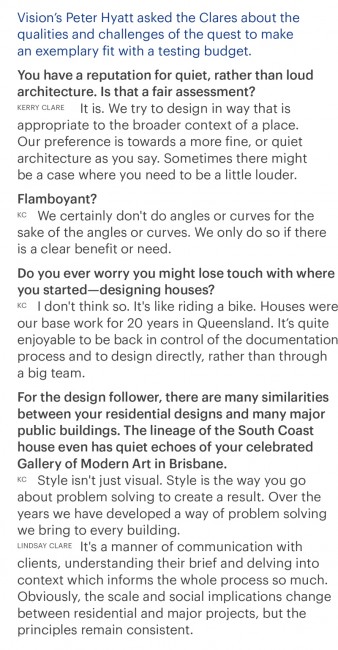

With this public library in Melbourne’s Docklands, Clare Design shows how a small, community-minded building can help instil a still-young urban precinct with a sense of place.

In the making of cities there are moments when all the pieces fall into place to create a sense of civitas. Until that time, many new, hugely scaled developments remain endless estates of undifferentiated floor space or ghostly mono-functional ghettoes – forlorn ventures that conjure the term “placeless.”

From Dubai to Shanghai, the world is currently full of such non-places, some built, thousands planned. Closer to home, we frown at Perth’s addled embrace of its urban fortunes and await Barangaroo – Sydney’s latest dalliance with urbs – with trepidation and a healthy dose of scepticism. In Melbourne, it’s been the same with Docklands – a long process of populating three windswept mini-coasts with high-rise apartments, massive offices for ANZ and NAB banks, and many saying behind their hands, “I told you so – this wouldn’t work – I wouldn’t live here.” But things have changed.

Docklands has become a city. It has places of exchange (two supermarkets and plenty of shops and restaurants as well as the huge offices). It has housing. It has a kindergarten and childcare centre (though not yet a school). It has an abundance of requisite public art, some of which has been specially designed to mitigate the chilly winds coming off the water. It even has its own stadium. And now, Lindsay and Kerry Clare of Clare Design have designed what might be considered this entire development’s true urban heart: a tiny public prism that may keep this new city alive.

The small library, which also contains within it a series of other public functions, is part of the City of Melbourne’s strategy of inserting or updating public libraries across the municipality. For Rob Adams, director of city design at City of Melbourne, each library was to be an urban exemplar, not just in terms of knitting together context, morphology and public space, but also in pushing the boundaries of technology, especially with regard to responsible environmental design. Adams commissioned Sydney-based architects Lindsay and Kerry Clare to investigate a series of hypothetical projects for various sites in Docklands, in effect testing the potential of this new city at Melbourne’s edge to embrace some form of civitas. The exercise was invaluable in demonstrating that the intervention of a small, community-based building could have significant impact. Places Victoria, the City of Melbourne and Lend Lease entered a tripartite agreement to deliver Victoria Harbour, including Dock Square and the library, which revert to City of Melbourne ownership and management.

In the end, the site chosen was at the hinge point of the central strip of dock in Victoria Harbour that is still to be developed. The Clares designed a three-storey rectangular box – each level with a floor area of 1000 square metres – and placed it close to the northern boardwalk. Critically, they added to the box a giant, north-facing verandah, a monumental gesture of welcome, climatically sensible, but also an echo of Melbourne’s archetypal public signifier since the 1840s: the urban verandah. These two gestures – placement on the site and the big verandah – were fundamental, as the building was being value-engineered to within an inch of its life. The Clares, working closely with Hayball in Melbourne on documentation and the City of Melbourne’s City Design on the interior fitout, developed the design to meet strict cost constraints and unusual construction challenges. Located on Victoria Harbour’s seventy-five-year-old timber piled wharf, the building had to be light and its weight evenly distributed. And so this new public building became a timber box, constructed almost entirely of cross-laminated timber (CLT): European spruce sourced from Austria and manufactured there in less than a week by Stora Enso. In addition to CLT, which includes the floor slabs, the building has been constructed with Glulam posts and beams, and recycled ironbark and tallowwood for the external cladding. The Glulam and CLT arrived in Melbourne packed into twenty-one shipping containers containing 1600 parcels, 110,000 nails and nearly eight tonnes of brackets – in short, a flat-pack building in the tradition of Swedish furniture giant IKEA. The building was then put together like a kit of parts and sheathed in the recycled timber, its edges detailed by the Clares with the precision of Prouvé and Chareau to create a breathing, self-ventilating box. With a series of features that includes a passive natural ventilation system supplemented by mechanical operable louvres on all four sides, 85 kW solar panels on the roof, water harvesting for flushing toilets, central skylights that act as ventilation chimneys, low VOC and formaldehyde materials, and all furniture and fitout meeting Green Star ratings – in addition to, surprisingly, minimal energy used in shipping the timber from Austria – the Library at the Dock was awarded Australia’s first 6 Star Green Star Public Building Design PILOT rating. This is no mean feat.

Given the Clares’ longstanding interest in design that is fit for climate, their shared experience of working for Gabriel Poole, Lindsay Clare’s childhood experiences of a Nissen hut on Bribie Island adapted for climate with the addition of adjustable window flaps, Kerry Clare’s admiration for the lean and clever spareness of Christopher Kringas’s 1960s design for her father’s Citroen car showroom in Sydney, and their environmentally careful design as design directors of Architectus for the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Brisbane, it is understandable that this little building was going to be, and is, dense with ideas.

First, the Library at the Dock is not just a library. In addition to its collection of 60,000 books, CDs and DVDs, it has multiple functions contained within it. At ground level, there’s a cafe on entry, as well as the necessary functions of information, book borrowing and return. Everything, including the columns, is timber, either left bare or stained black. It’s an effective palette as the spines of books and magazines lend the interior the rest of its colour. On the bleak Melbourne day I visited, the library felt Scandinavian. I could have been in Denmark. This had as much to do with the architecture as with the relaxed and informal functions that were added onto the library program. On the first floor is a gallery that can be hired out. On the second floor at the western end is a 120-seat theatre space with retractable seating. On the same floor there’s a recording studio as well as a semi-outdoor terrace where a father and son were playing table tennis on artificial grass, and where louvred walls and roof can open up to the park view and the sky for natural ventilation. In the dedicated kids’ reading area there are delightful, child-scaled curving shelf units designed by the Clares that recall the space-making strategies of Aldo van Eyck.

Architecturally, the unifying element within all of this is the nine-tonne central stair. Craned into place and with the feel of a packing crate transformed artlessly into an elegant public stair, this is the other elemental public signifier of the project, something the Clares refer to in their work as “open invitations.” The Clares don’t over-intellectualize their work and it is this strategy that imparts a relaxed humility to their buildings generally. In Docklands, the Clares’ building takes on a role that a municipal library took on in the suburbs in the 1950s but with extra functions: an unassuming identity that will become an intrinsic component in building community. A simple idea perhaps, but it is a strategy that lifts this project to a level of significance to which others aspire but do not reach. And fundamentally this is because of the rigour of its responsible making and the complete satisfaction of its brief. This little building is quiet in form and language but loud in its urban ambition. Given its already high usage (60,000 visits in the first three months), it is indisputable proof of a beating moment in a place about to find its heart.

Architect: Clare Design

Architect of Record: Hayball

Words: Philip Goad

Images: Clare Design, Dianna Snape, John Gollings

Posted: 2 Apr 2015

Source: Architecture Australia – January 2015 (Issue 1)

Tags: Civic, Public

Australian Achievement in Architecture Awards

The Institute’s inaugural Australian Achievement in Architecture Awards were held on 18 March at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane. The “people-based” awards event was led by the Gold Medal and included the presentation of the Neville Quarry Architectural Education Prize, the Bluescope Glenn Murcutt Student Prize, the Dulux Study Tour winner, the Colorbond Student Biennale winner, the Student Prize for the Advancement of Architecture and a new award, the Leadership in Sustainability Prize.

2010 GOLD MEDAL

SIMPLICITY, LIGHT, SPACE

Lindsay and Kerry Clare are this year’s Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medallists. We present a tribute with essays by Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper, Elizabeth Watson-Brown and Peter Mould and testimonials from Kenneth Frampton, Michael Bryce and Paul Thomas

Jury Citation

The Gold Medal is the Australian Institute of Architects’ highest accolade. It recognizes distinguished service by Australian architects who have designed or executed buildings of high merit, produced work of great distinction resulting in the advancement of architecture, or endowed the profession of architecture in a distinguished manner.

Lindsay and Kerry Clare have made an enormous contribution to the advancement of architecture and particularly sustainable architecture, with a strongly held belief that good design and sustainable design are intrinsically linked.Since starting practice in 1979, Kerry and Lindsay were key to pioneering the regional style associated with the Sunshine Coast. They are widely regarded for projects that display contextual sensitivity, clarity of design and environmentally sustainable principles.

Their projects have won prestigious awards, including twenty-eight state and national awards from the Australian Institute of Architects for housing, public, educational, commercial and recycling projects.

In the late nineties, Lindsay and Kerry left their office on the Sunshine Coast, and joined the New South Wales Government Architect’s Office as Design Directors. In two years they achieved many design successes in urban contexts and made an impact with buildings such as the No. 1 Fire Station in Sydney City. Since that time they have been founding design directors with Architectus. Here they have produced a highly significant cultural building, winning the design competition (with James Jones) for the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) in Brisbane.

Major awards include the 2008 AIA Queensland Public Architecture Award for the University of Sunshine Coast Chancellery, the 2007 RAIA National Public Architecture Award for GoMA and the RAIA Robin Boyd Award in 1992 and 1995. The recently presented 25 Year Award for Enduring Architecture (Queensland State Awards) for the White Residence, designed while in practice with Ian Mitchell, is a testament to the quality and longevity of their work.

The essence of the Clare design philosophy comes through in the GoMA, where simplicity, light and spatial qualities combine to produce a building of timeless elegance, which will serve the public well into the future.

Kerry and Lindsay Clare are highly respected and contributing members of the architectural profession. They have been actively associated with the Institute, participating on a number of committees. Kerry was also a national awards juror in 1999 and 2004, and a national councillor from 2000 to 2002. Lindsay was a national awards juror in 1996.They have always been willing to give time to furthering architectural education and were Adjunct Professors to the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sydney from 1998 to 2005. Kerry is a member of the City of Sydney Design Advisory Panel, providing advice on public and private developments to maintain high standards of urban design. She also serves on the Design Review Panel (SEPP 65) for Randwick and Waverley Councils, where she assists in the review of development applications, assessing their contribution to urban design, environmental, social and aesthetic issues.

Their great body of work demonstrates an appropriate environmental response, developing the concepts of efficient low-energy, sustainable solutions decades before legislation made it mandatory. Their Cotton Tree social housing project was selected as one of ten worldwide for inclusion in Ten Shades of Green in New York: an exhibition demonstrating architectural excellence and environmental sensibility organized by the Architectural League of New York. In 1996, this project received the RAIA Multiple Housing Award and the National Environment Citation. In 2001 they received the Energy Efficiency Award from the Urban Development Institute of Australia for the National Environment Centre. In 2009, the University of the Sunshine Coast Chancellery received the Institute’s Harry S. Marks Award for Sustainable Design.

Their work has been included in over 150 national and international books, periodicals and publications. They have been exhibited widely – in New York, Tokyo, Sydney, Melbourne and Perth, and in the 1991 and 2008 Venice Biennale, the1996 Milan Triennale and the 1996 UIA Congress Barcelona. The Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane is included in the Phaidon Atlas of Twenty-First Century World Architecture.The Clares’ work is extensively featured in a new book, Architectus: Between Order and Opportunity by Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper.

The Australian Institute of Architects recognizes and honours Kerry and Lindsay Clare as the 2010 recipients of the Gold Medal.

2010 Gold Medal jury

:

Melinda Dodson (chair), Howard Tanner, Adjunct Professor Ken Maher, Sue Phillips, Professor Gordon Holden.

Making existence meaningful

Lindsay Clare was born in Brisbane in 1952. He enrolled in quantity surveying at the Queensland Institute of Technology (QIT) and completed four years of the course before deciding to transfer into the Diploma of Architecture program. As a part-time architecture student, he worked on the Queensland Sunshine Coast in the office of Gabriel Poole, where he met his future wife and partner, Kerry Clare.

Kerry Clare was born in Sydney in 1957; her father was an industrial pattern maker, mechanic, inventor and owner of a Sydney Citroën dealership. As a teenager she lived in pre-Cyclone-Tracy Darwin, before enrolling in the part-time architecture course at QIT.

Lindsay Clare grew up sleeping on the verandah of a vernacular Queenslander house. During her teens, Kerry Clare lived in Darwin in a standard government house with entire walls of louvres designed to ameliorate the tropical climate without airconditioning. These childhood experiences of how to adapt houses to the climate were reinforced during their apprenticeship to Gabriel Poole.

In 1979, after working with Poole for almost five years, they established a practice (later to be called Clare Design) on the Sunshine Coast. Their early work was mainly residential and small commercial and institutional projects. With ten architectural citations and commendations during the first ten years of practice, they quickly earned a reputation for elegant and constructively expressive lightweight houses with interiors bathed in natural light and cooled by natural ventilation.

During the mid-1980s, the Goetz House (1984–85) and Thrupp and Summers House (1986–87) brought national recognition. The houses are significant milestones on the Clares’ path to aesthetic consistency and formal clarity. Of the Goetz house, Professor Michael Keniger says, “Despite being modest in size, this small house demonstrates a startling clarity of resolution and responds directly to the imperatives of place-making. Here, the enclosure of dwelling is stripped back to spaces directly derived from the two analogical sources of ‘cave’ and ‘bower’ … Within there is an almost obsessive rigour to the separation of served space from service space, and enclosed space from open … [An east–west] backbone is provided by the axial gallery. To the south [of it] are the ‘caves’ of fair-faced blockwork housing utilities … On the north are the ‘bowers’ of stick and panel, of glass and [flywire] mesh that shelter the living and sleeping spaces.”1 In 2008 John Gollings photographed the Thrupp and Summers house. His pictures capture the essence of the Clares’ contemporary modernism. The house is so lightweight that it seems to float in its bush setting. To the keen eye, the structure is rational and legible, yet its presence is recessive, an almost subliminal pattern, enough to suggest an order and rhythm that establish scale and proportion, depth and dimension. The interior is a light-filled volume composed from a limited palette of honey-coloured natural timber and fair-faced concrete blockwork set against a background of surfaces reduced to white planes washed by natural light. The long north-eastern wall of continuous full-height glass louvres dissolves the barrier between inside and out: house as abstracted verandah. The coolness of the Queensland verandah and a sense of cross-ventilating breezes, typical of the Clares’ architecture, are almost palpable in Gollings’ images. Looking at them, you would assume this house to be the very latest demonstration in a long line of elegant subtropical coastal houses designed by the Clares. But while Gollings photographed the house in 2008, it was actually designed and built more than twenty years before – and could have been designed by the Clares at any time over the past twenty years.

The Clares’ work attains timelessness. The architects eschew those popular architectural gestures that unerringly date so many contemporary buildings. Their approach to architecture is guided by a set of commonsense rules of thumb: buildings must respond to the climate and topography of a place; legibility is desirable and best achieved with simple forms sheltering, ideally, under a big roof; and the finishes of materials, the manner of their fixings and the junctions between them should express their inherent nature. For more than thirty years, the Clares have applied this approach.

In 1991 their McWilliam House (1989–90) was shown at the Venice Biennale. In 1992 their own Buderim House (1990–91) won the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) Robin Boyd (National) Award for houses – as did the Hammond Residence (1993–94) in 1995. Between 1982 and 1997, the Clares also won the RAIA Robin Dods (Queensland House of the Year) Award an unequalled six times.

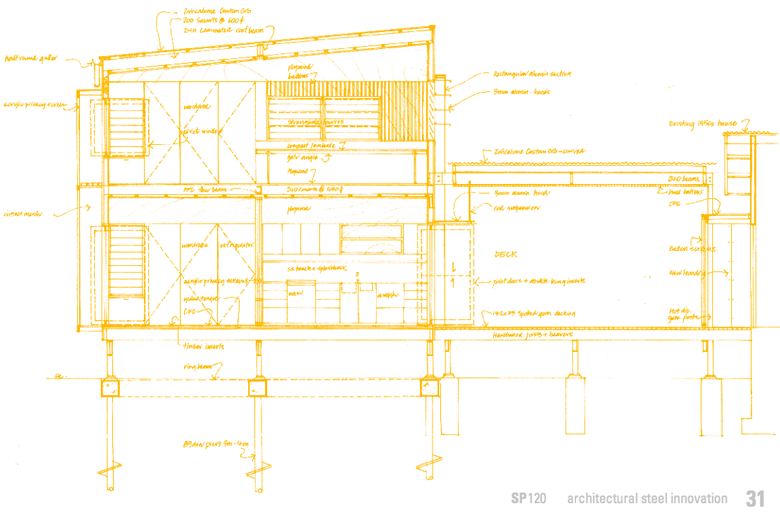

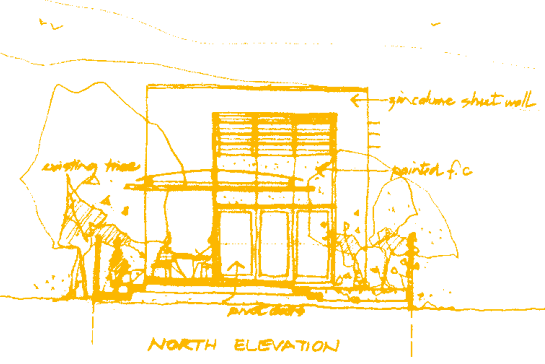

The Clares designed their own house as an experimental speculative development, a prototype for “a low-cost alternative to the fully tailor-made house”. Peter Hyatt describes it as follows: “To achieve low construction costs, the structure … [is] a two-storey timber box, framed and braced by plywood ‘fin’ walls along the perimeter. These fins form alcoves … useful areas for entry, storage or work [benches] … No internal walls are required for bracing or load bearing … The house [has] a loose-fit skeletal structure that can be clad and subdivided according to site, program and material preference.”2 Structurally, the house is a timber box. Formally, it is a tin box, but one with multiple readings that combine to give the whole an air of lightness. The roof, no more than a thin plane of corrugated iron, appears to have been draped over the top of this box and anchored by sculptural downpipes; the long sides, slightly thicker planes of corrugated iron, are not so much attached to the box as propped up against it; and at either end, brightly painted cement sheet boxes read as the ends of a longer but smaller box protruding from the larger box. At each end, the dark painted wall surfaces between these two boxes, and between them and the roof, can also be read as void. The apparent fly-away layered lightness of the whole is further reinforced by the floating planes of corrugated iron that form the roofs over the terraces and the carport.

Two works of the early 1990s added to their repertoire of innovative typologies for subtropical housing and low-impact environmental design: Rainbow Shores (1990–92) and Cotton Tree Pilot Housing Project (1992–95), which won the national RAIA Environment Citation (1996). This latter work was chosen in 2000 from an international field of “green” buildings for inclusion in the Ten Shades of Green exhibition in New York, an exhibition demonstrating architectural excellence and environmental sensitivity organized by the Architectural League of New York. Herbert Muschamp, architectural critic of The New York Times, wrote that it was “the most romantically utopian project on view … The most utopian aspect … is its atmosphere of social and spatial informality. It picks up on the direction in which American architects were headed in the postwar years, when California’s Case Study Houses, designed by Charles and Ray Eames and others, wove spare, modern design into the West Coast landscape … Why should the Australians run away with a style of living that began with Frank Lloyd Wright?”3 In 1998 the Clares were appointed Design Directors to the NSW Government Architect. The move to Sydney provided opportunities to work on larger projects than was possible in regional Queensland and the chance to teach, as adjunct professors in the University of Sydney Faculty of Architecture (1998–2005).

The Clares left the NSW Government Architect in 2000 to become founding directors of Architectus Sydney in 2001, a federation of architectural practices formed from offices based in Auckland, Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. In the same year, now as design directors of Architectus (and in conjunction with James Jones), they won an international competition for Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA, 2001–06; RAIA National Award for Public Architecture, 2007).

In many respects, GoMA is a defining work: a significant civic building that encapsulates the Clares’ architectural position and design strategies. The plane of the big roof echoes the siting of the building on the river flats, reinforcing local perceptions of place. Typologically, it is a big box under a big roof – a recurring formal theme in their work, and a building form reminiscent of both the traditional Queenslander and the backyard shed (both familiar types). The campus planning ordered around cross-axes of circulation is also typical. Along the cross-axes, natural light is introduced from above and at the edges of the building. The cross-axes/campus planning strategy is a flexible, loose-fit strategy that corresponds with their aesthetic approach to building finishes, which is also loose-fit. The Clares produce an architectural poetic based on expressing all the finishes as layers floating over the structure. The layering and overlapping of surfaces overcome imprecision and cover up mistakes in an often roughly assembled underlying carcase. For the Clares, layering is both a loose-fit aesthetic and a very practical loose-fit way of constructing buildings.

An art gallery is required to be a sealed airconditioned box. Consequently, although GoMA is shaded, the Clares were denied the opportunity to introduce natural ventilation into the building. This central aspect of their design position was addressed in their next major civic building, the Chancellery for the University of the Sunshine Coast (2003–06), which adheres to all the design strategies observed in GoMA and incorporates a sophisticated system of active natural ventilation – such that it won both the Australian Institute of Architects Queensland Public Architecture Award and the Harry S. Marks Environment Award (2008).

The climatic strategies are largely ones tried and tested over many years by the Clares in their domestic work, here scaled-up and mechanized. Sunhoods – similar to ones they have used in houses, but much longer – shade windows. On its southern side, the entire building opens to form a shady civic-scaled verandah that captures the prevailing south-easterlies. To enhance cross-ventilation, the deep plan is a campus of buildings separated by “external” streets, all under a single roof with vented skylights. To minimize the impact of solar gain on the thermal mass of the building, masonry walls are clad with a weatherproofing and sunshading skin (reverse veneer) of either corrugated iron or cement sheet. In the heat of summer, when the windows in the seminar rooms and staff offices are opened to admit the north-easterlies, electric relays automatically shut down the local split-system airconditioning units and open high-level louvres on the leeward side of the room.

For larger-scaled commercial projects, the rules-of-thumb principles and simple passive controls used for domestic buildings are not enough: a more scientific approach is necessary. The Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) has developed the Green Star Office Design rating tool, a holistic environmental rating scheme for commercial buildings that measures environmental performance over a range of criteria including water and energy consumption, materials, indoor environmental quality, site considerations, emissions, transportation and the long-term environmental management of a building. On a six-star rating scale, five stars denotes a degree of excellence that surpasses the top quartile of the industry.

Wesley House, a slender ten-storey office building in the heart of Brisbane (completed in 2009 in association with Fulton Trotter Architects), achieves a five-star rating. It features chilled beam technology with a 100 percent fresh air supply; fixed shading “blades” on all glazed facades (computer-tested); fritted double glazing with low-E glass; water-efficient fittings, using rainwater harvesting for toilet flushing; bike racks and showers for cyclists; low-emission interior finishes, recycled construction materials and the recycling of construction waste; computer-generated studies for optimum day lighting; and a building user guide, an environmental management plan and post-occupancy evaluation and tuning.

Wesley House does not overtly express its green credentials. With the exception of the sunshading blades, much of the Clares’ attention to environmentally sustainable design (ESD) is concealed from view. And even the blades read not so much as sunshades but as a delicate tracery of lines that form the urban-scaled backdrop to the little red brick Neo-Gothic church that stands in front – a bit of the city’s Victorian heritage left stranded, like a fish out of water, by the surrounding high-rise offices.